TDEE Calculator for Weight Loss

This TDEE calculator does more than just estimate your daily calorie needs—it also analyzes your ideal weight, sets personalized fitness goals, and provides a complete meal plan and weekly workout routine to support your journey.

TDEE Calculator

Want to lose weight fast? Start by finding your daily calorie needs with a tdee calculator. Knowing your TDEE helps you set the right calorie goal and keeps you safe.

Research shows that keeping track of your energy use is key for weight loss and avoiding regain.

Always check your TDEE before changing your diet.

Key Takeaways

-

Calculate your TDEE to understand your daily calorie needs. This helps you set a safe calorie goal for weight loss.

-

Aim for a calorie deficit of 500 to 1000 calories below your TDEE for effective weight loss. This can lead to losing 1 to 2 pounds per week.

-

Regularly check your TDEE every 6 to 8 weeks or after significant weight changes. Adjust your calorie intake as your body changes.

What Is TDEE

TDEE Meaning

TDEE means Total Daily Energy Expenditure. It is the number of calories you burn each day. You use energy for things like breathing and moving. You also use energy when you eat food. Experts say TDEE is the energy you use in one day.

Your TDEE comes from a few places:

-

Resting Energy Expenditure (REE): This is 60% to 70% of your TDEE. Your body uses this energy to stay alive when you rest.

-

Thermic Effect of Food (TEF): This is about 10%. Your body needs this energy to break down food.

-

Activity-Induced Energy Expenditure (AEE): This has two parts:

-

Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (EAT): This is about 5%. It comes from planned exercise.

-

Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (NEAT): This is 15% or more. It comes from things like walking or fidgeting.

-

Why TDEE Matters

Knowing your TDEE helps you start losing weight. You can use a tdee calculator to see how many calories you burn. This helps you pick a calorie goal that works for you.

Many things change your TDEE. Here is a quick chart:

|

Factor |

Description |

|---|---|

|

This is most of your energy use. It gets lower as you age. It gets higher if you move more. |

|

|

Thermic Effect of Food (TEF) |

This is about 10% of calories burned. It comes from breaking down food. |

|

Physical Activity (PA) |

This can be 30-80% of calories burned. It includes all movement, not just exercise. |

If you know your TDEE, you can plan how much to eat. People who track their TDEE often lose more weight. They also keep the weight off longer.

How to Use a TDEE Calculator

Gather Your Info

You need some basic facts about yourself before you start. This helps the tdee calculator give you the best answer. Here’s what you should have ready:

-

Weight

-

Height

-

Age

-

Gender

-

Body fat percentage (if you know it)

-

Activity level (how much you move or exercise each week)

You can find most of this information in your health app. You can also check your last doctor’s visit. If you do not know your activity level, think about how much you walk or work out each day.

Enter Data in the TDEE Calculator

Now you are ready to use a tdee calculator. There are many online tools and apps that do the math for you. Just type in your details and let the calculator do the work.

Here are some of the most trusted online calculators:

|

Calculator Name |

Method Used |

Accuracy |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Mifflin-St Jeor |

Mifflin-St Jeor Equation |

High |

Most accurate for general use, validated in studies |

|

Katch-McArdle |

Katch-McArdle Equation |

Higher |

Best if you know your body fat percentage |

|

Harris-Benedict |

Revised Harris-Benedict Eq. |

Moderate |

Less accurate than Mifflin-St Jeor |

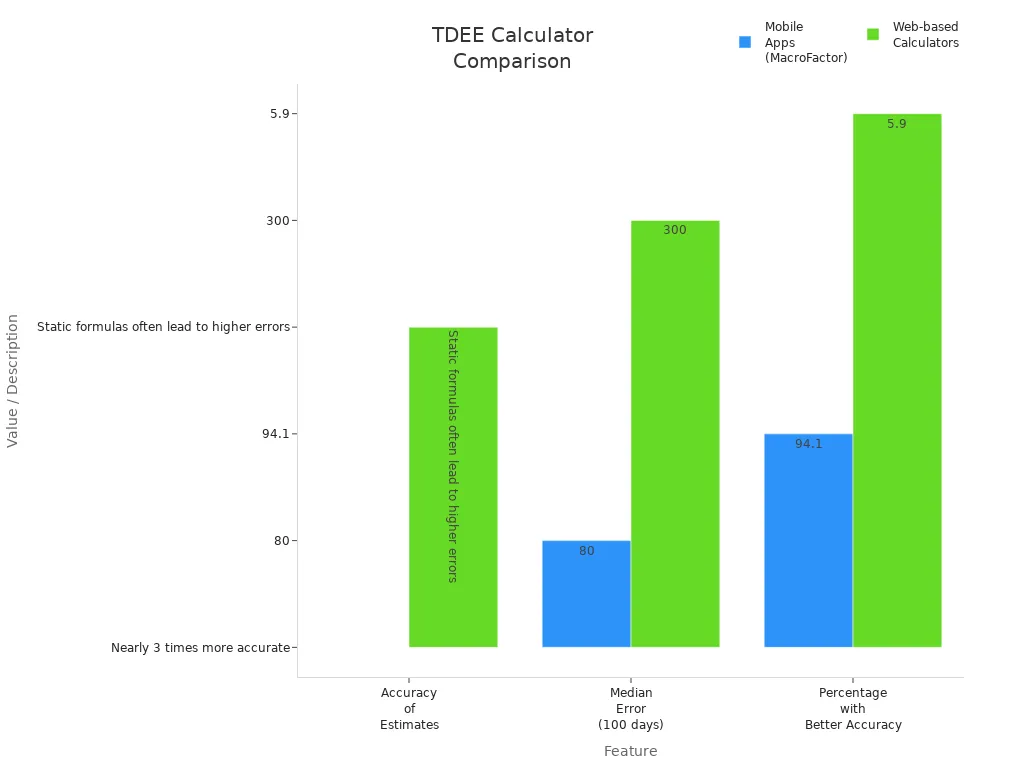

If you want even better results, try a mobile app like MacroFactor. Mobile apps use smart technology and get better as you use them. They can be almost three times more correct than web calculators. Most people see a mistake of only about 80 calories per day. Web calculators can be off by 300 calories or more.

|

Feature |

Mobile Apps (MacroFactor) |

Web-based Calculators |

|---|---|---|

|

Accuracy of Estimates |

Static formulas often lead to higher errors |

|

|

Median Error (after 100 days) |

~80 Calories per day |

~300 Calories per day |

|

User Experience |

Adaptive algorithms improve over time |

Static formulas do not adapt |

|

Percentage of Users with Better Accuracy |

94.1% |

5.9% |

Read Your Results

After you enter your info, the tdee calculator gives you some numbers. You will see your TDEE, BMR, and sometimes BMI. Here is what they mean:

-

BMR (Basal Metabolic Rate): This is the energy your body needs to stay alive when you rest.

-

TDEE: This is your BMR plus calories burned from moving, eating, and exercise.

-

BMI (Body Mass Index): This shows if your weight is healthy for your height.

Most calculators use the Mifflin-St Jeor equation for BMR. This way is better than old formulas, so you get better results for your weight loss plan.

Your TDEE has four main parts:

-

BMR: Energy for basic body needs.

-

NEAT: Calories burned from things like walking or cleaning.

-

TEF: Energy used to digest food.

-

Exercise Activity: Calories burned during workouts.

Set Your Calorie Deficit

To lose weight, you need to eat less than your TDEE. This is called a calorie deficit. Experts say you should eat 500 to 1000 calories less than your TDEE for safe weight loss. This helps you lose about 1 to 2 pounds each week.

-

A calorie deficit means you eat less than you burn.

-

Your calorie needs depend on your sex, age, activity, height, weight, and body shape.

-

You can make a deficit by eating less, moving more, or both.

Cutting too many calories is not safe. It is better to make a small, steady calorie deficit of about 200-500 calories below your TDEE. This helps you lose weight safely and keeps your body healthy.

Adjust for Weight Loss

Your body changes as you lose weight, so your calorie needs change too. You should check your TDEE every 6 to 8 weeks or after big changes in your weight or activity. If you lose 10% of your weight, check your numbers again. If you start a new workout, update your TDEE.

Here is how to keep your plan working:

-

Subtract 500-1000 calories from your TDEE for your daily goal.

-

Watch your progress and change your calories if you stop losing weight.

-

Check your TDEE again after big changes in weight or activity.

Studies show people who change their calories after weekends or routine changes lose more weight. Keeping your calories steady on Mondays and weekends helps you reach your goals. Eating most of your calories earlier in the day may help your body use energy better.

Tip: Track your calories and weight every week. If you stop losing weight, eat 100-200 fewer calories or move more.

Apply Your Calorie Goal

Plan Meals

Meal planning helps you stick to your calorie goal and makes healthy eating easier. Try to fill your plate with 80% healthy foods and keep treats to just 20%. Add lots of fruits and veggies for vitamins and fiber. Lean proteins like chicken, fish, or eggs help you feel full. Whole grains and healthy fats, such as avocados and nuts, give you lasting energy. Drink water or herbal tea to stay hydrated.

-

Include protein-rich foods to keep you satisfied.

-

Choose high-volume foods like fruits and veggies for fullness.

-

Mix protein, carbs, and fats in each meal.

-

Add beans, lentils, and whole grains for fiber.

Track Calories

Tracking what you eat keeps you honest and helps you spot patterns. Start by logging your meals in an app like MyFitnessPal, Cronometer, or FatSecret.

MyFitnessPal has a huge food database and makes calorie tracking simple. Cronometer gives you detailed info on nutrients. FatSecret offers a free version with a barcode scanner and meal planning tools.

Weigh your food or use measuring cups to get portions right. Log meals daily and review your week to see where you can improve.

Monitor Progress

Check your weight often to see how you’re doing. Daily weighing works best for most people and helps you notice changes quickly.

|

Method of Self-Monitoring |

Findings |

Impact on Weight Loss |

|---|---|---|

|

Daily Weighing |

Linked to more weight loss |

More frequent weighing leads to better results |

|

Weekly/Monthly Weighing |

Still helps, but less effective |

Less frequent weighing may slow progress |

Avoid Common Mistakes

Don’t cut calories too much. Eating too little can slow your metabolism, make you tired, and weaken your immune system.

|

Health Risk |

Description |

|---|---|

|

Lowered Metabolism |

Eating too few calories can slow calorie burn by up to 23%. |

|

Fatigue and Nutrient Deficiencies |

Not enough food can cause tiredness and low nutrients. |

|

Weakened Immunity |

Too few calories may make you get sick more often, especially if you work out a lot. |

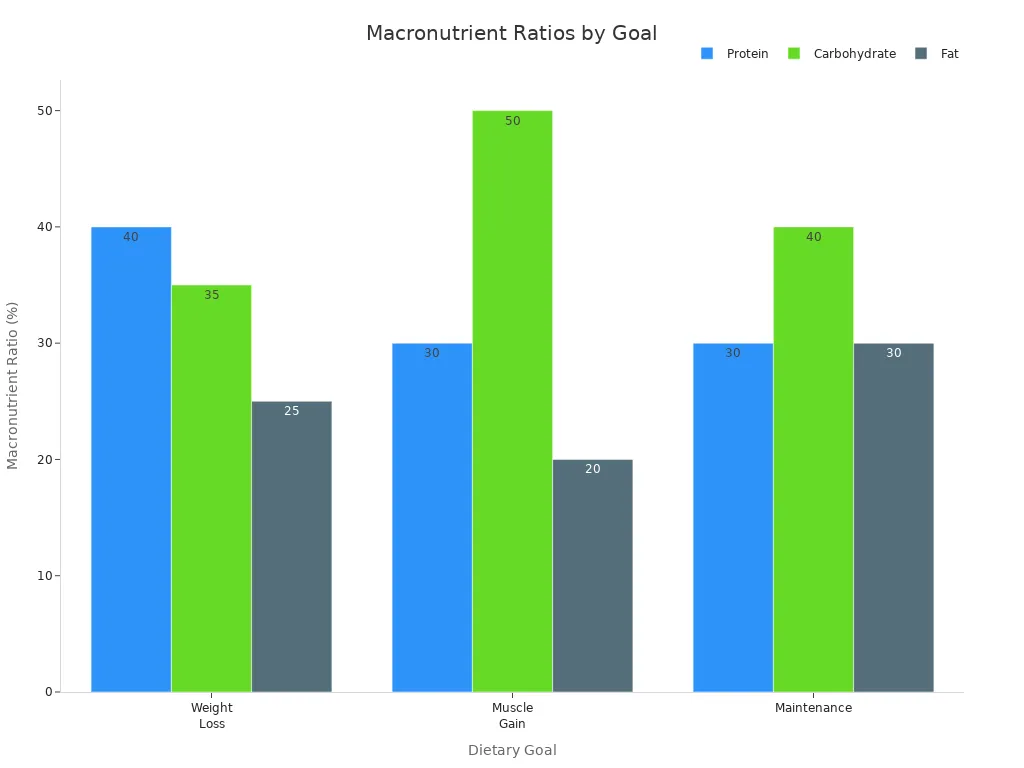

Balance your meals with the right mix of protein, carbs, and fats. For weight loss, aim for about 40% protein, 35% carbs, and 25% fat.

|

Goal |

Protein Ratio |

Carbohydrate Ratio |

Fat Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Weight Loss |

40% |

35% |

25% |

Apps make tracking easier and help you stay on target. Celebrate your wins and adjust your plan as you go.

You can lose weight quickly if you use a tdee calculator. Set a calorie deficit and make small changes each day. Being consistent is the most important thing for long-term results.

-

Keeping your calories the same helps you reach your goal.

-

Watching what you eat and planning meals keeps you motivated.

|

Strategy Type |

Description |

|---|---|

|

Dietary Strategies |

Eating more fiber helps you feel less hungry. |

|

Behavioral Strategies |

Tracking what you eat and planning ahead help you succeed. |

Start now. Take your first step and see your progress get better!

FAQ

How often should you recalculate your TDEE?

You should check your TDEE every 6 to 8 weeks or after big changes in your weight or activity level.

Can you use a TDEE calculator if you don’t know your body fat percentage?

Yes! Most calculators work fine without body fat percentage. Just enter your age, weight, height, and activity level.

What if you stop losing weight after setting your calorie goal?

Try lowering your calories by 100-200 or add more movement. Track your food and weight to spot what’s slowing your progress. 🏃♂️